Enzyme prevents brain activity from getting out of control

Mechanism identified at University of Bonn alters the coupling of nerve cells

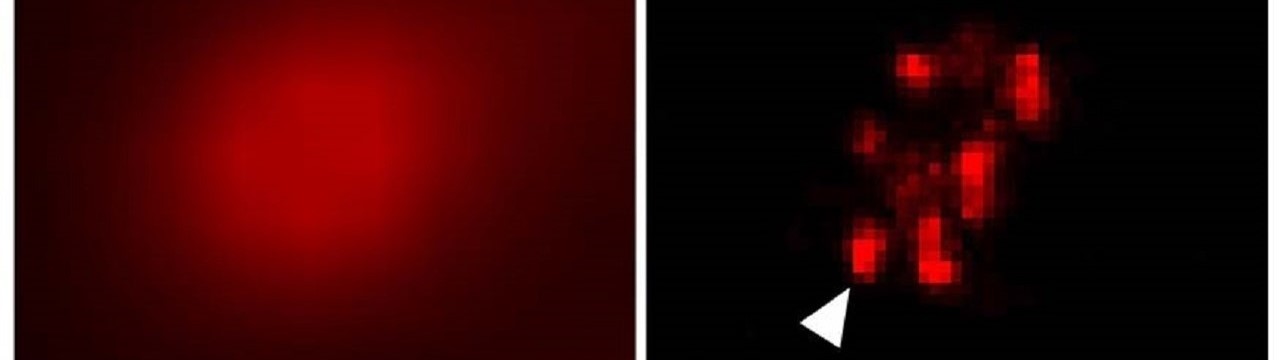

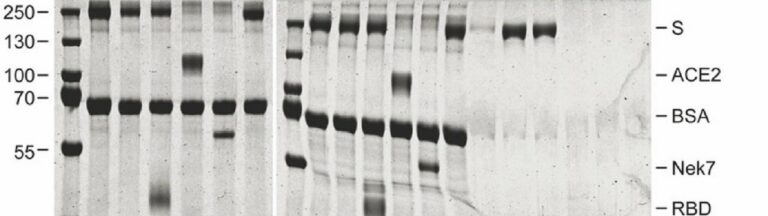

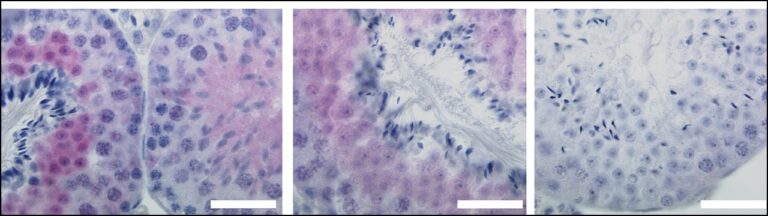

The brain has the ability to modify the contacts between neurons. Among other things, that is how it prevents brain activity from getting out of control. Researchers from the University Hospital Bonn, together with a team from Australia, have identified a mechanism that plays an important role in this. In cultured cells, this mechanism alters the synaptic coupling of neurons and thus stimulus transmission and processing. If it is disrupted, diseases such as epilepsy, schizophrenia or autism may be the result. The findings are published in the journal Cell Reports.

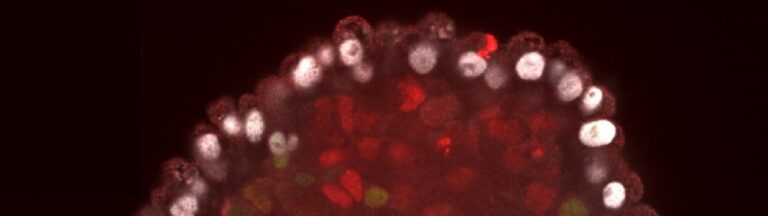

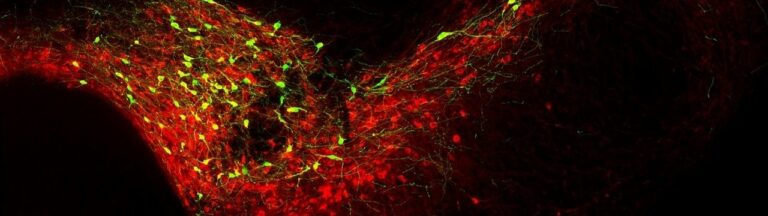

Almost 100 billion nerve cells perform their service in the human brain. Each of these has an average of 1,000 contacts with other neurons. At these so-called synapses, information is passed on between the nerve cells.

However, synapses are much more than simple wiring. This can already be seen in their structure: They consist of a kind of transmitter device, the presynapse, and a receiver structure, the postsynapse. Between them lies the synaptic cleft. This is actually very narrow. Nevertheless, it prevents the electrical impulses from being easily transmitted. Instead, the neurons in a sense shout their information to each other across the gap.

For this purpose, the presynapse is triggered by incoming voltage pulses to release certain neurotransmitters. These cross the synaptic cleft and dock to specific “antennae” on the postsynaptic side. This causes them to also trigger electrical pulses in the receiver cell. “However, the amount of neurotransmitter released by the presynapse and the extent to which the postsynapse responds to it are strictly regulated in the brain,” explains Prof. Dr. Susanne Schoch McGovern of the Department of Neuropathology at University Hospital Bonn. […]

Participating Core Facilities: The authors acknowledge the support from the Microscopy, Mass Spectrometry, and Virus Core Facilities.

Participating institutions and funding:

The study was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG), the BONFOR program of the University Hospital Bonn, the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), and the Cancer Research Foundation and Cancer Institute New South Wales. In addition to the University and the University Hospital Bonn, the University of Sydney and the Australian company i-Synapse were involved in the work.

Publication: J. A. Müller et al.: A presynaptic phosphosignaling hub for lasting homeostatic plasticity; Cell Reports; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110696